I love monsters.

I love how they look, how they act, the stories they lurk through, the kind of fear they inspire, the kind of fear that inspires them—I love it all. My favorite literature is Gothic, my favorite films are horror; it is all due to the stories the monsters tell in them. From Dracula to Friday the 13th, I claim all monsters as my own, in one way or another, and I endeavor to understand them, their makers, and their cultural markers.

I fell in love with Frankenstein the first year of my master’s degree because I decided that the Creature was a story in himself, and the story that contained him revealed truths about Mary Shelley’s world and culture to such a degree that I think I began to understand the Creature immediately. I once wrote a paper titled “Am I My Other’s Keeper?; or, Sympathy for the Creature.” In it, I break down how Victor Frankenstein’s monster is a figure of cultural difference, his treatment is an enactment of Othering, and his story should illicit sympathy in its readers because he did not choose to be made, misunderstood, or mistreated. He was the opposite of someone’s “self” and thus made monstrous—something that happens every day in the modern age. I identified with him, and I understood why the culture that created him was the monster, not the Creature himself.

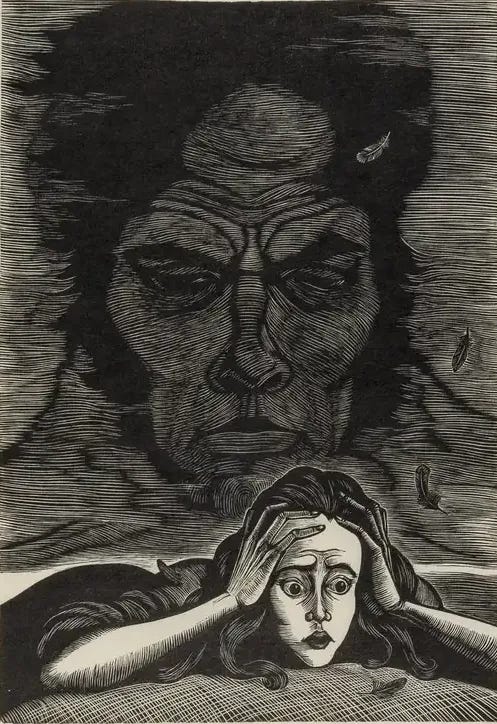

This evolved into a deep dive into “monster theory” or “monster culture,” which is the study of monsters as cultural avatars; this framework is designed to help readers and scholars understand cultures from the monsters that they create, and vice versa. According to monster culture—and the seven theses that I will soon break down—every monster, creature, and critter is the product of its culture, and its existence hints at the potential for a new shift in that culture.

For something to be a monster, it must be feared. For something to be feared, it must pose a threat. For it to pose a threat, there must be a cultural “norm” to destabilize. To destabilize that norm, something must be monstricized.

And this is what makes a culture’s monsters.

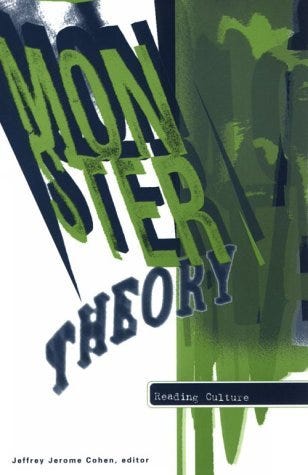

Monster culture was introduced by Jeffrey Jerome Cohen in 1996, when he edited a collection of essays analyzing monsters in literature and film as the truth tellers of a culture, entitled Monster Theory: Reading Culture. Cohen’s introduction “Monster Culture (Seven Theses),” is known as “the introduction to a volume that named a field… allowing dispersed scholarship to coalesce around its banner and start to form into something coherent.” His theses provided a framework for the future of monster studies.

In Monster Theory, scholars and critics engage with their disciplines through Cohen’s framework, entangling seemingly disparate topics—Icelandic aliens, conjoined twins, even Jurassic Park—with monster theory. They use monster culture to analyze why societal norms and exceptions exist, what causes cultural shock and awe, and even why we have such a hard time constructing our sense of self in the modern age.

So what do our monsters have to say to us?

“Monster Culture (Seven Theses)”

Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s “Seven Theses” are a set of theoretical propositions (what he calls a “new modus legendi,” or way of reading) that can be used to explore the cultural, social, and psychological functions of monsters in literature, media, and mythology. These theses are foundational in the field of monster theory, and as monster studies develop, they have become most useful as building blocks rather than laws for reading into how monsters reflect society—its fears, flaws, constructs, and contradictions.

Thesis 1: The Monster’s Body is a Cultural Body

Monsters are cultural constructs that embody society’s collective fears, anxieties, and desires. They represent the boundaries of the human experience but also indicate that which is considered Other, such as social, racial, sexual, or gender differences.

In philosophy, “Other” refers to anyone or anything perceived as distinct or different from oneself. There is the self and there is the Other, which is simple enough because that’s how everyone inherently constructs their identity and engages with the world. I am the only Me, and so everything that isn’t that is Other than Me. This gets a little sticky when we think about how we build larger concepts of the self by identifying with parts of ourselves.

Think about how Americans construct the world—there is America and there is everything else. That which is part of America would become part of the “self,” and everything outside of it (or different from a particular person’s definition of “America”) is Other. If someone builds up an “American self” in their mind that only includes white, English-speaking, domestically-born people, then anyone who is non-white, non-English speaking, and not domestically born is the Other.

Othering is not a good thing, is the point. It’s what fosters division, dehumanization, and discrimination (see: Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s “Can the Subaltern Speak?”). When cultures come together to create monsters, they do so through the lens of Othering. Why was Dracula exoticized? He’s a vampire, which is already non-human, so why does his identity as a Transylvanian nobleman matter to his monstrosity?

Short answer: Xenophobia.

Long answer: Dracula literally feeds off of the novel’s “natives” (the British), and his parasitic relationship with those characters signals a cultural anxiety regarding people from foreign cultures “sucking” away British culture. Dracula’s body—the monster’s body—reflects the culture that created him, specifically because the culture felt the need to create him.

Thesis 2: The Monster Always Escapes

Monsters cannot be fully understood or contained. They exist at the margins of human understanding and defy easy categorization, so we can’t even contain them in our own minds. But even when monsters are defeated in narratives, their symbolic power continues to haunt society.

Why are there so many adaptations of Frankenstein? Why does the Creature look different in each one? Why do we not get confirmation that he dies, even at the end of the original novel? He always flees to the margins of the text, only returning to the centerfold when it again becomes necessary for him to terrify the next reader, adapter, or generation.

Think of the symbolic power of Frankenstein in general. The novel was originally written at the peak of Weird Victorian Medical Practices, and people were genuinely convinced that they could bring dead things back to life with electricity (see: Victorians’ weird history with frogs).

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley—being the child of a women’s rights advocate and a political philosopher—obviously knew what she was doing when she invented the ‘mad scientist’ archetype. Through Victor Frankenstein, she asks what happens when you try to play God, when you try to have life without women, when you take advantage of nature and then neglect to nurture it, etc.

But think about how these concerns—and the monsters that embody them—have escaped into modern thought: We’ve gone from genius-gone-mad Victor Frankenstein to genius-billionaire-playboy-philanthropist Tony Stark; from a patchwork of corpses to walking corpses aka zombies; we have Norman Bates as just the absolute embodiment of mommy issues; artificial life in the form of robots taking over and killing us for mistreating them; and so on forever.

Frankenstein’s “monster” is actually societal fears about the unknown and the uncontrollable, and what happens when society finally has to face them. And that anxiety has persisted—and escaped—through centuries.

Thesis 3: The Monster is the Harbinger of Category Crisis

Monsters challenge conventional categories and definitions, such as the human/non-human or the natural/supernatural. Their existence blurs boundaries and creates a crisis in how societies define themselves and the Other.

How do you define yourself? How do you define that which is Other? Is it just as simple as “human vs. not” or “living vs. not”? Do you understand what those categories mean? What happens when they get mushy and something—say a minotaur who is half-man-half-bull—shows up, telling you that those categories actually aren’t distinct, the lies can be blurred, and your current understanding of order in the world is now null?

Zombies are one of my favorite examples of category crises because their mere existence is so paradoxical and uncategorizable. What do you mean by “living dead”? Things are supposed to be either living or dead, never both, right? If something is dead, it should stay dead, according to the categories we have about life and death. What you would think is the most basic definition of life and death is troubled by their existence, and that is why it troubles us so much.

I also think about the werewolf, here. It cannot be categorized as either a man or an animal because it is both, like the Minotaur. The Wolfman is a bit more disconcerting, though, since he isn’t human or non-human—and because his humanity and animality wax and wane with the moon. He is neither nor and never either, so can only consistently be defined as Other and monstrous.

Humans are driven by logic (…most of the time). Our brains like patterns and labels because they help us understand things. If something cannot fit into a singular box, then we can’t understand it, and in a world as big as ours, not understanding can be scary.

Thesis 4: The Monster Dwells at the Gates of Difference

Monsters represent the fear and fascination with difference, whether it is racial, sexual, cultural, or other. They are often the result of social anxieties about groups or individuals that exist outside of established norms, but that are still present in society.

Monsters are often racialized and sexualized because those happen to be the most commonly feared differences in society. In Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847), Heathcliff is described as having dark skin and features, and his origins are unknown; he’s called a foreigner, and he is dangerous because of it, according to the other characters. No one knows where he’s from, what race he is, or what that means for their distinctions of self/Other. And to return again to my Dracula example, Heathcliff’s sexual “deviance” is a large part of his monstrous identity, and the fact that he “preys” on white women is a large part of what makes him such a threat (I’ll let you all read up on miscegenation in your own time).

Disability studies have also had a very resonant voice in the topic of monstrous difference because so many monsters in literature and film have monstricized disabilities. In the Friday the 13th lore, Jason Voorhees has hydrocephalus and is presumably neurodivergent. Hydrocephalus is a fluid buildup in the brain, which is what caused Jason’s head shape to appear altered or enlarged; this condition is also most likely what caused his developmental disabilities. The horror of Jason comes in part from his appearance, but also from his mental difference. If he doesn’t look or think the same as “us,” then how will we ever know what to expect from him? He is a physical and cognitive Other.

Thesis 5: The Monster Polices the Borders of the Possible

Monsters function as a means of regulating social norms and acceptable behaviors. They often emerge in stories that reinforce societal boundaries, warning individuals not to transgress those limits: not to make a mad scientist of themselves in the name of playing God, not to transgress sexual norms by falling for the seduction of a vampiric foreigner, etc. In this way, they are the “monstrous border patrol” of social order.

Think back to Frankenstein’s Creature. He kills everyone in Victor’s life as if he’s mocking and reminding him: ‘If you hadn’t played with the laws of nature, I wouldn’t exist; If you hadn’t created me, I wouldn’t have brought suffering into you or your family’s life.’ The Creature is telling Frankenstein that he went too far beyond what should have been “possible,” and so he must be punished for it. He’s like Hippocratic border control for scientists whose britches got too big.

Thesis 6: Fear of the Monster is Really a Kind of Desire

The fear that monsters elicit is often tied to a deeper, unconscious desire. Monsters are simultaneously repulsive and alluring; they embody forbidden desires or forbidden knowledge, suggesting that the line between fear and attraction is often blurred. This also serves to remind us that human wills and whims are vulnerable in the face of Otherness, and our natural inclination to move toward it is something potentially dangerous.

I told myself I wouldn’t bring up Twilight, but I feel legally obligated to discuss why we have so many attractive monsters and what they tell us about the culture we live in. I mean, think about why Bella wanted to be a vampire? She wanted to live forever and be with Edward forever, and she wanted a family that wouldn’t abandon her, the Cullens. Her desire, then, was for life eternal, something accessible through vampirism. She wanted the sparkly skin and strength and beauty that came with it all, too.

But what about the not-so-sparkly romantasy monsters? Well, they still offer us a narrative opportunity for taking part in the “darker” parts of life, like true crime and people’s ongoing fascination with serial killers and slashers, even. Despite their horrific crimes, humans tend to love thinking about and understanding the darker side of human nature, and engaging with the monstrosity of their crimes (via podcast, books, documentaries, whatever) gives the average person the chance to indulge their fascination, but safely. Same with most modern horror movies: we get to indulge in the outright gore and terror that their stories offer without having to face the real-life consequences of confronting them (see my post about emotional catharsis for more info on why our monkey brains like danger-at-a-distance).

Thesis 7: The Monster Stands at the Threshold… of Becoming

Finally, Cohen tells us that monsters represent the ongoing potential for transformation, both on the personal and cultural level. They symbolize what is on the horizon or in the process of change, whether that be science on the brink of creating humans, the racial/sexual Other “sucking” away the vitality of British/heteronormative culture, or the turn towards no longer fearing but now romanticizing the monstrosity that offers an average girl from Forks some kind of liberation.

Monsters mark moments of transition in a culture or era, and they warn us of a future that can only ever be filled with potential shifts—whether that change is regressive or progressive, the monster cannot say. The stories that deliver them to us are often the tellers of this truth for readers.